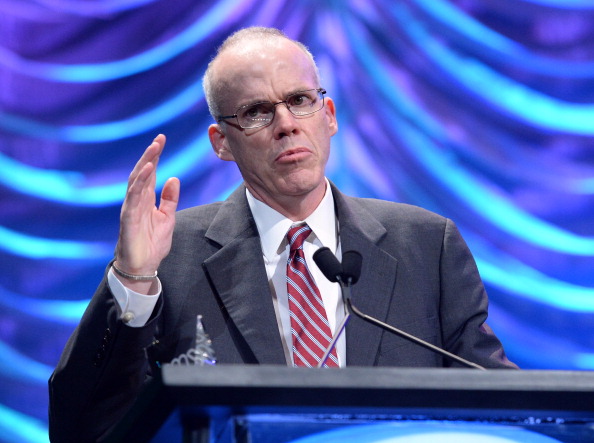

In his August 2019 piece in the New Yorker, well-known environmental activist Bill McKibben attacked the use of wood biomass for electricity generation. His central claim? That utilizing wood biomass is as harmful to the climate as fossil fuels.

McKibben’s claim flies in the face of the scientific community’s consensus on wood biomass. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – the gold-standard authority on climate science – has repeatedly affirmed that wood bioenergy is necessary in any climate change mitigation strategy. More than 100 university scientists recently agreed, penning a letter concluding that wood biomass energy “yields significant net decreases in overall carbon accumulation in the atmosphere over time compared to fossil fuels.” Both the UN and leading university scientists also underscore the need for forest markets to incentivize growing more trees. In other words, if private landowners can make money growing and replanting trees, they will do so.

So how does McKibben come to the opposite conclusion? The answer lies in a fundamental error in his assumptions about carbon sequestration – he examines the issue from the perspective of an individual tree and ignores the broader forest landscape.

McKibben conceives of wood biomass as follows:

Trees, of course, are carbon—when you burn them you release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. But the logic went like this: if you cut down a tree, another will grow in its place. And, as that tree grows, it will suck up carbon from the atmosphere—so, in carbon terms, it should be a wash.

He continues,

Burning wood to generate electricity expels a big puff of carbon into the atmosphere now. Eventually, if the forest regrows, that carbon will be sucked back up. But eventually will be too long—as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change made clear last fall, we’re going to break the back of the climate system in the next few decades. For all intents and purposes, in the short term, wood is just another fossil fuel, and in climate terms the short term is mostly what matters.

Here’s the issue: this is a narrow and short-sighted explanation of how wood biomass works, and if McKibben makes incorrect assumptions, it’s no wonder he comes to a false conclusion.

First, McKibben examines a tree that is used for wood biomass, and assumes that from that individual tree’s perspective, utilizing it for energy expels carbon now, while sequestration from a new tree grown in its place takes a long time. Sure, that makes sense for an individual tree. But the reality is that carbon emitted by a tree used for wood biomass is simultaneously reabsorbed by the growing forest landscape.

Wood biomass is a small part, about 3% of the total annual harvest in the U.S. Southeast, of a vast and highly-sustainable forest products industry. Due to strong demand, privately owned forests are growing some 40% more wood than they harvest, capturing more carbon than is released by all wood product uses, including biomass. So it’s not an individual tree that matters, but rather what is happening in the forest as a whole.

If the forest as a whole is growing and sequestering carbon faster than what is lost from removals, the system as a whole is producing significant carbon savings compared to fossil fuels.

This leads to McKibben’s second error – he examines wood biomass in a vacuum, and ignores that it plays a small, but necessary, role in a low-carbon future.

Yes, wood biomass produces some carbon emissions. But it produces significantly fewer emissions than widely-used fossil fuels, which is why organizations like the United Nations note that it is a necessary component of the global effort to mitigate climate change. Experts at both the University of Georgia and the University of Illinois find that wood biomass reduces carbon emissions compared to coal by approximately 80 percent on a lifecycle basis.

This then begs the question – why not simply utilize carbon-free energy sources like wind or solar? The answer lies in the power system itself. Wood biomass produces baseload energy, energy that supports the backbone of the power grid and can be quickly ramped up or down depending on demand. Solar and wind are intermittent power sources, they don’t provide baseload energy. In other words, wood biomass energy complements solar and wind by replacing coal, the dirtiest energy source and currently the baseload source of energy for much of the world. They are not comparable energy sources, but rather complementary ones. Moreover, wood biomass is one of the easiest ways to achieve lower-carbon baseload energy, since existing coal plants can be quickly retrofitted to run on wood biomass in a cost-effective manner.

Unfortunately, Bill McKibben’s piece in the New Yorker fails to grapple with these realities. That’s a shame, because when someone of Bill McKibben’s stature spreads distorted claims about an industry that is today actively replacing tons of dirty coal energy as a power source, it sets back global efforts to replace fossil fuels and chart the path to a lower-carbon energy future.